Giornata: BWV 1004 #5; Quartet F maj op. 135 Es Muss Sein!

2016

16×20

Oil on linen

Painting notes:

For those of you out there [hello!] who might want a bit of clarification:

Giornata is an art term, originating from an Italian word which means “a day’s work.” The term is used in Buon fresco mural painting and describes how much painting can be done in a single day of painting.

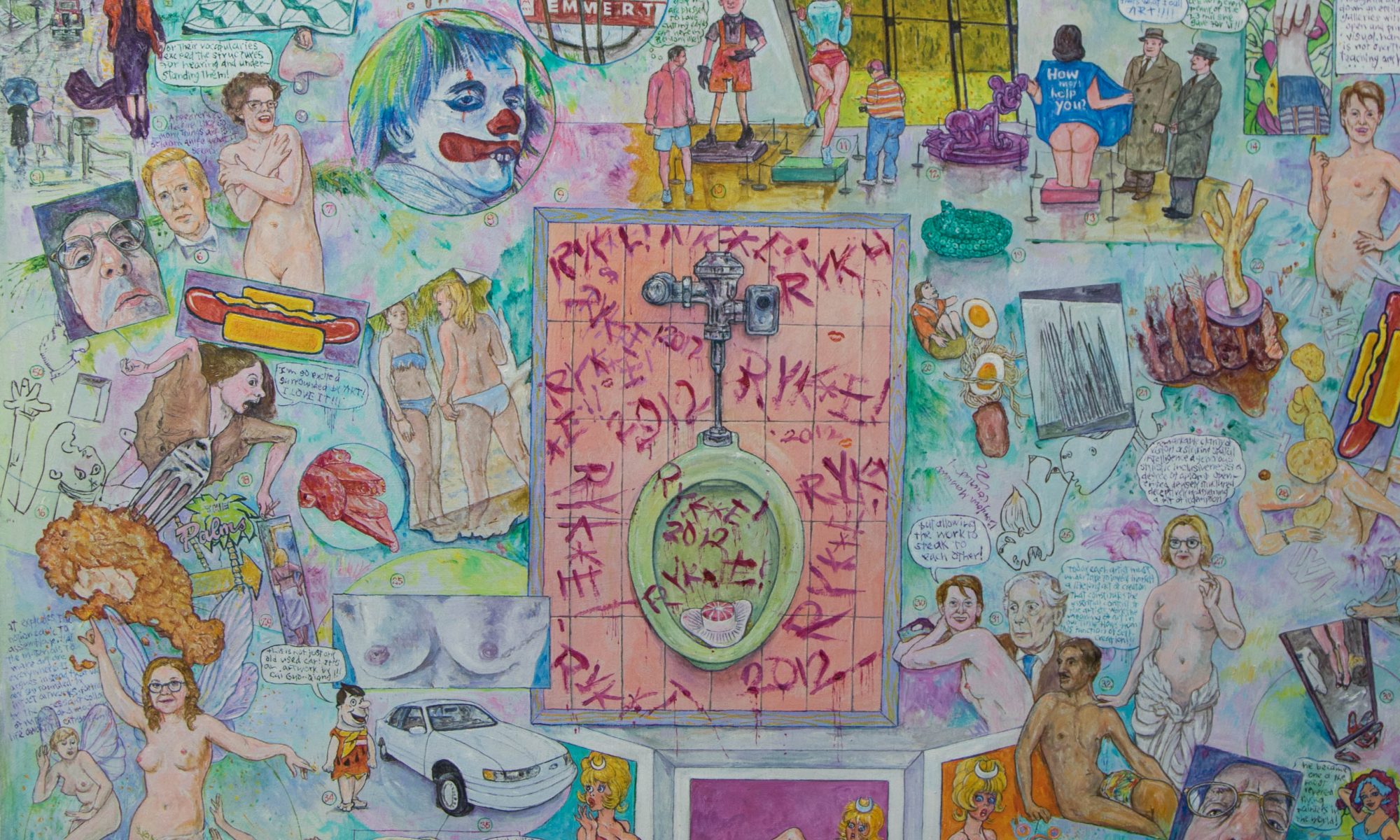

I like the sound of the word; it describes in a way how I proceed. I start with an image which suggests other ideas. It might be a correspondence of meaning or of shape and I enjoy seeing where it goes as a novelist will say after a point the characters take over. I had been thinking about the injustice of the Rosenbergs, how the current crop of GOP candidates resembles the McCarthyites, air raid drills, A. Warhol using Old Sparky as an art objet, Ingres’ fabric and that of a tawdry costume, my disgust with the art, art babble, the bomb as a beautiful flower, Damien’s dumb pickled shark, my nose [Gogol] with a formica laminate base waiting for a museum appearance… An indigestible mix of high and low.

The attitude returns me to my formal art training when I was inner directed up until, say high school, before the confusion of art hystery. My subjects were an expression of what bothered me, contrarian protest. After the storms of my business interlude I’m doing what I please for my own amusement. Heard enough?

The music are last pieces, my state of mind.

- My Colonoscopy

- The Rosenbergs

- J. Edgar

- Damien’s The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living, 1991. Put that in your ear Ludwig!

- Aperçu from Roberta Smith.

- Damien’s The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living, 1991.

- Dicky N.

- Aperçu from Frank Stella.

- Ingres: The Princesse de Broglie, 1853.

- Atkinson Grimshaw: Park Row, Leeds, 1882.

- Anon, poster: The War of the Worlds, 1953.

- Egon Schiele on his death bed, 1918.

- Rudyard Kipling: The Conundrum of the Workshops But the Devil whoops, as he whooped of old: “It’s clever, but is it Art?”

- Ingres: Baroness James de Rothschild, 1848.

- 32 Street Car – The Celestial Omnibus’

- Anon, poster: The Band Wagon, 1953.

- Broken age. – Victorian cemetery monument updated.

- 1Bernini: Ecstasy of Saint Teresa, 1652.

- Ethel Rosenberg.

- Anon. poster: Patricia Owens, The Fly, 1958.

- Kiki of Montparnasse.

- William Blake: Tyger.

http://thebeethovenproject.

Kerman (The Beethoven Quartets, 1966) suggests the comedy, which is so apparent in the Allegro, already starts in the “Muss es sein?” introduction, imagining characters from commedia dell’arte:

To my ear the image is operatic enough: a recitative for Pantalone, punctuated first by dubious stirrings (Mélusine perhaps?) and the by blustering chords in the upper instruments (the Spanish Captain Spavento?). The scoring suggests an opera orchestra, but in a gauche way that has to be understood as parodistic (or self-parodistic: Beethoven could have been thinking of the Ninth Symphony) … None of this is very funny, perhaps – with Beethoven, the broader the joke the less effective – until Es muss sein! timidly acknowledges the piteous roar in the low instruments … To this comedy the Allegro offers no serious answer. As one of those deft demonstrations of analytic philosophy, the question is rephrased and shown never to have amounted to a true question in the first place.

de Marliave (Beethoven’s Quartets, 1928) thinks along similar lines:

[T]he mysterious preface was enough to intrigue the curiosity of listeners and critics, who see in it as a result a meaning that it does not possess. The argument shares the defect of all such attempts to set a ‘programme’ to absolute music.

And says about the finishing bars of the coda:

It is though Beethoven is laughing at himself and at his audience for taking this little motif so seriously, and making such a mystery out of his whimsical Muss es sein? which was no enigma at all!

Sullivan (Beethoven – his spiritual development, 1927) suggests that the motto

is a summary of the great Beethovenian problem of destiny and submission. But Beethoven had found his solution to the problem, and he treats the old question here with lightness, even the humour, of one to whom the issue is settled and familiar. There is no real conflict depicted in this last movement; the portentous question meets with a jovial, almost exultant answer, and the ending is one of perfect confidence. The question raised here is, indeed, seen in the light of the profound peace which dominates the slow movement of this quartet. If we may judge from this quartet [….] it would appear that at the end of his life the inner Beethoven who expressed himself in music, was content.

However, Lockwood (Beethoven – the Music and the Life, 2003) offers more extensive thoughts on the subject. He encourages us to take Beethoven’s question seriously, and highlights the fact that Beethoven struggled with its exact wording: he initially hesitated between “der gezwungene Entschluss” (the forced decision) and “der harte Entschluss” (the hard-won decision) before settling for the one we know. He asks:

What is the meaning of the inscription? We do not know, and are not meant to know in any specific sense, what is being asked and answered. We cannot miss the feeling that something basic is afoot, but we cannot define it in words or concepts. That may be the point. As in the Ninth Symphony’s cello-bass recitatives and at various points in other late works, Beethoven is driving instrumental music to the limits of speech, making instruments ‘almost speak’ …

He points out that, according to Karl Holz, Beethoven used to speak in an “imperial style” and speculates that:

It is not far-fetched to imagine Beethoven asking and answering the question ‘Must it be?’ to himself and perhaps to others, expecting no explanation and giving none.

Some final thoughts

Regardless of whether Beethoven intended Op. 135 to be his final statement or not, and in spite of any possible textual explanations of the “Muss es sein?” riddle, I find it hard to see its over-all effect as anything other than profound. The two last movements especially together give a strong sense of coming to terms, and if the quartet is an intermezzo, it gives an impression of being one between this life and the next. And, contemplating the very end, what better way to go than with a bang?

The two Graves in the last movement, with their “Muss es sein?” motif, do perhaps give a certain theatrical impression, and maybe they also seem to induce the feeling of being slightly too serious for their own good (this is obviously in no way a criticism of Beethoven!), but as a player, when actually playing them, I find it hard not to take them seriously, whatever the question might mean. As soon as the answer appear in the Allegro, the question is immediately put in a new light, but it can, for me, only in hindsight be regarded with a smile.

The Allegro has by some commentators being characterised as either “ironic” or “forced”, but in my eyes the completely honestly good-natured second theme certainly excludes the former idea, even if the recurring “Es muss sein!” statements have a certain touch of jauntiness. If it is forced, it is in the most humorous way. And the little coda marks the ending (and indeed the whole piece), twinkly-eyed and humorous as it might be, with honesty and kindness.

Lockwood writes:

“For Beethoven, as for the greatest literary artists, above all his beloved Shakespeare, comedy is not a lesser form than tragedy but is its true counterpart, the celebration of the human in all things.”